To gauge how fast Nairobi, Kenya is growing I could look up at the glass and steel rising to fill the empty spaces in its skyline but I spend more of my time looking down at my feet.

To gauge how fast Nairobi, Kenya is growing I could look up at the glass and steel rising to fill the empty spaces in its skyline but I spend more of my time looking down at my feet.

I've only been in Kenya's capital city for a little more than a month yet the dusty dirt paths I take on my 20-minute walk to Grameen's Ngong Road office are being transformed into sparkling, sculpted concrete sidewalks seemingly overnight. This expansion is a mixed blessing for at least one of the shoeshine stands that line this major Nairobi thoroughfare - or so the gentleman trying to revive my dirt-covered shoes explained.

The statistics support what I'm seeing on and in the ground. Construction was a major driver of Kenya's more than five percent growth in GDP during the first quarter of 2013 increasing 13.5 percent over the same period last year and followed by 6.7 percent year-over-year growth in Q2. That's tons of cement poured on streets like the Kilimani Ring Road I plod along Monday through Friday.

Installing traffic lights, however, doesn't seem to be moving at the same pace as paving. It feels like I'm tempting fate each time I cross Ngong Road avoiding swerving Matatus (privately owned minibuses that bring many Kenyans to work) buzzing motorbikes and speeding 4x4s. You'd think I'd be prepared for pedestrian roulette having grown up in New York City and navigated Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue, Ocean Parkway and some of the city's other dangerous streets. But I'm not. Each attempt to cross these roads offers a fresh moment of fear and exhilaration.

Not far from my office on Ngong Road is a place where paved roads, no matter how chaotic, are a luxury. The Kibera slum, whose population has been estimated anywhere from 200,000 to nearly one million people, is one of if not the biggest slums in Africa. The Economist magazine says it "may be the most entrepreneurial place on the planet" if for no other reason than the need of its residents to survive. It has been a focus of NGOs, social enterprises, government organizations and others trying to chip away at its poverty. I hope to visit it soon and to give you my impressions in future blog posts.

TaroWorks

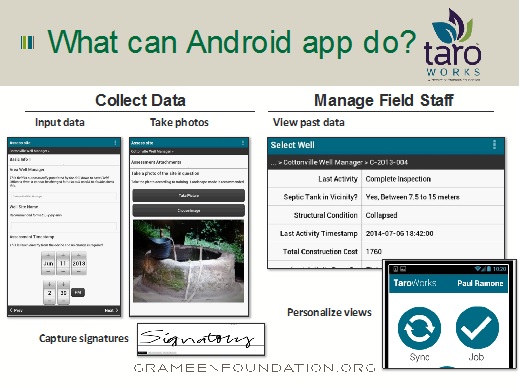

Organizations attempting to meet the pressing needs of Kibera residents are the kind of groups I'm working with during my one-year Grameen Foundation Fellowship at TaroWorks in Nairobi. TaroWorks, a unit of Grameen, sells a mobile technology solution to social enterprises and NGOs that helps them run and scale their field operations through real-time data collection, powerful business analytics and performance management tools.

Our customers face challenges managing their remote field force like no cell phone or Wi-Fi service, legacy data collection methods that rely on paper or spreadsheets which limit growth and difficulty assessing the performance of their teams at long distance. They also crave real-time data that can give them business insights but can't afford expensive and complex analytics systems.

My assignment is to identify potential TaroWorks clients and make a compelling case that our product will help them overcome these and other obstacles. We organize TaroWorks' capabilities in three core areas: managing a social enterprise, monitoring its impact and knowing its customers. Our clients are resourceful, committed to their mission and sophisticated in their understanding of how data and mobile technology can help transform the work they do. My colleagues have created a lean startup within a larger organization and developed a culture that stresses iteration, innovation and open communication.

At a time when businesses are debating whether their teams are more effective working side-by-side or remotely, the TaroWorks team makes a case for the value of a distributed workforce. During our weekly product roadmap meeting team members dial in to Google Hangouts from Nairobi, Jakarta, Seattle, San Francisco and Washington, DC. Online collaboration tools keep us productive while flexibility, focus and a sense of humor keeps things moving forward - even when a weekly business development meeting can end just before dinner for some people or just after breakfast for others.

After Work

One of the things I looked forward to living and working in Kenya was experiencing a culture much different than mine. That’s been the case in so many ways from food, to tribal politics to social norms. In a few instances, though, I haven’t felt far from home. Indoor and outdoor shopping malls showcase many of Nairobi’s retailers and are a meeting place for Kenyans and ex-pats. Visit the Nakumatt superstore at Junction Mall and you can buy a toilet brush or a wedding gown. Having breakfast in the Art Café late one morning before seeing a first-run movie at Junction, I heard a Norah Jones song from the restaurant’s sound system, turned to my wife and asked her to make sure we weren’t in Paramus, New Jersey.

Just about 30 minutes from Junction by car, however, is Nairobi National Park, 28,000 acres of game preserve within the city limits that is a world away from Times Square. Gangly giraffes rise up to nibble tree limbs in the shadow of the city’s tallest buildings, herds of zebra graze under the hot sun and lions lumber through the tall grass. And that’s just in the first 45 minutes.

If you need another sign you’re in a different world, a traffic sign in the park’s public parking area says it all:

“Speed Limit

20 K.P.H.

Warthogs & Children

Have Right Of Way”

Howard Sherman is a Business Development Fellow, based in Kenya.. Check back for more about Howard's experiences in the field.